Jun 9, 2017 / by Nancy Cruz / In Socio eco-cultural, Vince Deschamps

Socio-cultural Values of Natural Capital – Valuing the invaluable

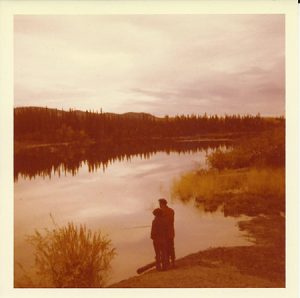

The Attawapiskat River pic was taken just upstream of the infamous (and dangerous) Second Rapids.

I left the Socio-cultural values discussion until the end of this valuation mini-series because I find that valuing the ecosystem services associated with them – namely Recreational and Cultural – quite challenging. As I indicated last month (albeit buried in the footnotes), I consider Recreational and Cultural ecosystem services to be “passive” consumptive services that should be exempt from economic valuation. But the question, once again, is how should they be valued?

Socio-cultural values emphasize the “human nature” component of a natural capital resource. As such, we should consider natural capital resources providing them as being:

“specific to the preferences of the beneficiary(ies) and expressed through land use practices and/or the likelihood of an ecosystem service being used. Some of these values are absolute; invaluable and irreplaceable (e.g., cultural or spiritual sites).”

Consuming a natural capital resource for Recreational purposes is obviously intended to evoke pleasurable experiences, and is a conscious choice made by the user. However, the need to engage in recreation is arguably a basic human function much like eating or drinking. The health benefits of recreating (and of not), are well documented in recent literature. I’m not a believer in the “Willingness to Pay” principle, as I don’t think it places value on the experience per se, rather it associates a cost with the equipment, facilities or infrastructure required to enjoy it. For example, one doesn’t pay for the experience of taking their dog for a walk in the forest, but they do pay for the leash, biscuits, and poopy-bags required to conduct said dog-walking. These costs do not (in my mind) represent the value of the experience of hiking with your favorite hound through the woods – SQUIRREL!!! The dog-walker could spend $25 on all of this and have a great experience, or could pay the same $25 and have a bad experience – the cost to access the resource is the same, but the value of the resource (and hence the experience) is much different. From this standpoint, it would boil down to what the resource means at a personal level, or how it is subjectively “valued” by the dog-walker (i.e., what characteristics do they look for in a forest when they choose to walk their dog there).

One way to value a natural capital resource (e.g., forest, lake, stream, etc.) that provides recreational ecosystem services would be to look at the relative importance of that resource in providing that service. This system of valuation could be in the form of an “index” which could build upon established means of quantifying the physical conditions of a resource. An example would be the Whitewater Classifications of rivers for a canoe and rafting experiences or the Rock Climbing Ratings of trails and cliffs for hiking and climbing. Given an appropriate set of measurable parameters – and depending on the users of the natural capital resource at play – it wouldn’t be too far a stretch to develop a forest classification that maximizes the experience of dog walking…poopy-bags notwithstanding. Any such classification approach should, however, focus on assessing/valuing the characteristics of the resource providing the service, and not assessing the experience itself.

Natural capital resources that provide Cultural ecosystem services are somewhat different and more intense, in that they are a result of who we are, and not just what we choose to do. Values associated with Cultural ecosystem services are hard-wired into our DNA at personal, community and societal levels and therefore tend to be absolute, and generally, cannot be replaced. As everyone interacts with nature differently, it makes assessing Cultural values difficult. I can think of three personal experiences to illustrate this.

- When I was nine years old, my parents and I drove across Canada and wound up moving to the Yukon. For five years, we enjoyed the unspoiled wilderness. As an only child, I developed a very strong bond with my parents on these forays and it obviously represented a very formative time in my life. One lake in particular – Tarfu – was a favorite spot where we spent many weekends camping and fishing either by ourselves or with others I was able to drag along. When I turned fifteen, Mom and Dad decided that we would move back to Ontario as it offered more in terms of my post-secondary education than was available at the time, even in Whitehorse. I packed up my fishing rod and we moved back. Fast forward to 1989 – I had just graduated from university and was working in Prince Albert National Park in northern Saskatchewan when Mom called and told me Dad was dying from cancer. When I got back to Ontario I spent as much time with Dad as I could, and I would regularly sneak him out of the hospital to go for long drives by his old fishing haunts until he got tired and I had to take him back. Much of our conversations during these rides were about the times we spent at Tarfu – although he knew he would never get back there, we both understood the importance of that place in how he raised me and taught me how to appreciate life and respect nature.

- The Cree people of northern Ontario and Quebec have been using the rivers leading into James Bay as travel routes for millennia. When I assisted the Attawapiskat First Nation to develop their Community-Based Land Use Plan, our team spent time with Elders learning how people lived as part of nature and were reliant upon it for their livelihoods. We were also fortunate enough to spend time with hunters from the community out on the Attawapiskat River – a massive waterway that extends several hundred kilometers upstream of the Bay. Families in the area have traditionally traveled back and forth on the river between summer fishing camps and winter hunting areas by means of canoes – now motorized, but previously paddled. Despite its incredible natural beauty, travel on the river is arduous, and portions notoriously perilous, such as the Second Rapids. Over time, people have inevitably perished on the long journey either from dangers associated with the trip, or simply because their time had come. In most cases, and for quite practical purposes, graves are typically located within 100 meters of the river, and their locations marked only in the memories of the Elders. Understandably, the Attawapiskat River is highly valued by the Attawapiskat First Nation, and other Indigenous communities in the James Bay area, given the traditional dependency on the river as a way of life, as well as the presence of spiritual and cultural sites along the shoreline.

- In the extreme south-western corner of the island of Java, in Ujung Kulon National Park, are a series of caves known as Sanghyang Sirah. Although most Sundanese and Javanese adhere to Islam, there remains an underlying animistic culture that still thrives throughout both cultures. The Sanghyang Sirah caves are a sacred site and widely recognized as where strong spiritual energies can be felt by those who make the pilgrimage to meditate and pray there. And a pilgrimage it is – there are no roads and worshippers must walk from Taman Jaya, which is approximately 35 kilometers from the caves (as the Hornbill flies) through the Park’s dense jungle, mangrove swamps and along a seemingly endless sand beach that is fully exposed to the hot equatorial sun and continuously pounded by the waves of the Indian Ocean. In order to arrive with a clear mind and demonstrate true devotion, the trek must be made without the benefit of food or water. Only once they have reached the caves are pilgrims allowed to eat or drink, and many have perished en route to Sanghyang Sirah, in search of inner peace and spiritual health. Having made the trip several times (albeit always as a researcher and never as a pilgrim), I always found myself in awe of those willing to put themselves through so much to get to Sanghyang Sirah, and respected the spiritual importance of the caves to their most basic of beliefs.

I’m sure that everybody reading this has similar reasons why they find themselves – either communally or individually, connected with the natural world, which is why the Socio-cultural values of natural capital may be the most important of all. They don’t put money in our pockets, and they probably don’t put food on the table. But, whether it’s the local forest where we walk our dogs, the milky water and ancient stone carvings of a Javan cave providing inner peace, the statue of the Virgin Mary providing comfort to those passing through the Second Rapids, or the little lake in the Yukon where I spread my father’s ashes, these places are bound to our most inner beings and are clear evidence that we are still part of the natural world, and not merely onlookers.

Vince and his dad, 1976. This photo was taken during a late summer evening on the shores of Tarfu.

Vince Deschamps is an ecologist and Registered Professional Planner with over twenty-five years of professional practice, including living and working in protected areas in rural and remote parts of the globe. Vince is at the forefront of developing Natural Capital and Ecosystem Service Assessment (NCESA) as a scientific discipline and has applied the approach in support of traditional land use systems and conservation initiatives in Indonesia, Barbados, and Ontario’s Far North.

More information is available on Vince’s LinkedIn page

You can also follow Vince on Twitter @VinceDeschamps

Vince can be reached by email at vince.deschamps@sympatico.ca